LIVING RESURRECTION:

an initiate's best-kept secret

Based on material from The Lost Art of Resurrection: Initiation, Secret Chambers, and the Quest for the Otherworld by Freddy Silva. ©2014. No unauthorized reproduction or sharing please.

Let me begin with a legend of a child, born in cave, saved from death in infancy, who grows up to teach a new religion to the masses, then removes himself to a wilderness for a prescribed period, and upon his return is killed on a wooden structure, only to resurrect three days later and be deified as a god. This legend is of a god-man from c.1800 BC called Krishna. Were you expecting someone else?

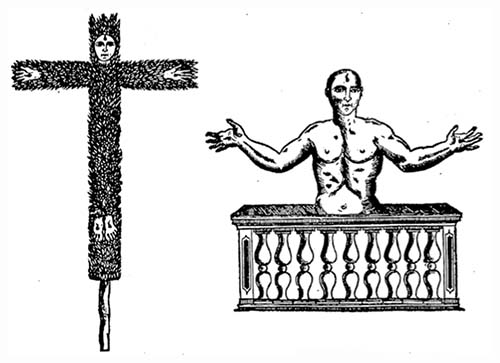

While there are 346 analogies between the story of Krishna and Jesus alone, there are at least eighteen other avatars around the world answering to above description. And what’s more, they all precede Christianity by 500 to 2000 years: Thammuz of Sumeria, Atys of Phrygia, Indra of Tibet, Iao of Nepal, and Wittoba of Java — a god-man nailed to a tree and symbolized by a crucifix. And not forgetting, of course, the god-man savior of the Maya, Quetzalcoatl, born of a virgin, indulged in a forty-day fast on a sacred mountain, atoned, rode an ass, is purified in a temple with water and anointed with oil, then nailed to a cross on a sacred hill, and rests in the Otherworld for three days before resurrecting. From Phoenicia to China the pagan world celebrated the hero who crosses into the Otherworld as a ‘dead’ man on the winter solstice, only to rise as a god three days later. Yet by the 4th century, fundamental Christians were eradicating evidence of such atoning god-men in order to exalt singular status upon the new hero Jesus, but alas, the idea had long been in vogue.

So why was the Church promoting Christ as a unique case? Part of the answer lies in the subterranean passage ‘tomb’ of Thutmosis III, a pharaoh from 1470 BC. Written upon its walls is a text called Treatise of the Hidden Chamber that provides instruction on how to proceed into the Otherworld, a parallel place that interpenetrates the world of the living. The Egyptians called it Amdwat. It is the place from where all physical forms manifest and to where they return. It is an integral component of birth, death and rebirth. Only through a direct experience of the Amdwat can a person grasp the operative forces of nature, the knowledge of which was said to transform an individual into an akh — a being radiant with ‘inner spiritual Illumination’.

Quetzalcoatl, also known as Kukulkan to the Maya, a crucified god-man on the Winter solstice.

All these instructions cover Thutmosis’ resting place. There’s just one problem: the instructions are meant for the living: “It is good for the dead to have this knowledge, but also for the person on Earth...whoever understands these mysterious images is a well provided light being. Always this person can enter and leave the Otherworld. Always speaking to the living ones. Proven to be true a million times.”

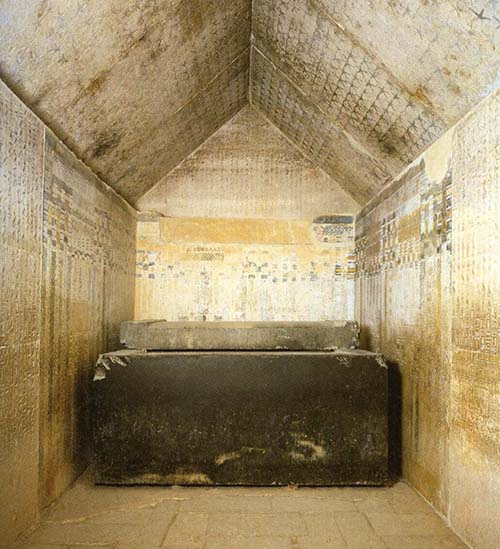

Thuthmosis’ chamber is anomalous: it features a well, a redundant feature for a dead person; its main room is aligned northeast, the traditional direction associated with enlightenment and wisdom; its oval sarcophagus is of superlative craftsmanship, and yet Thutmosis was buried in the temple of Hatshepsut.

Thutmosis isn’t the only case of absent burial. When the step pyramid of Sekhemkhet was excavated, its entrance and chambers were still sealed, including its alabaster sarcophagus, and when opened it was found to contain nothing but air; the same situation occurred at the pyramid of Zawiyet el-Aryan. Two Old Kingdom pyramids, un-burglarized, with no body inside: evidence that not all funerary buildings were intended as final resting places but served some other, possibly ritual purpose.

To ancient Egyptians, a tomb was considered a place of rest but not necessarily a pharaoh’s final resting place, just as experiencing the Otherworld did not require a person to be dead. Rather, evidence shows that, following a secret rite of initiation, the candidate was roused from a womb-like experience and proclaimed ‘risen from the dead'.

The Pyramid Texts covering Unas’s chamber give detailed instructions on leaving the body and returning alive.

Sekhemkhet’s pyramid lies in Saqqara, a sprawling ceremonial temple complex named for Seker, falcon god of rebirth. The name arises from sy-k-ri, the cry made by the god of resurrection Osiris as he wanders through the darkness of the Otherworld seeking to unite with his bride Isis. And indeed it is here where the earliest surviving works of sacred literature offering a unique ritual experience connecting a living person with the Otherworld are found — in the subterranean tomb of Sekhemkhet’s neighbour, the pharaoh Unas.

The Pyramid Texts contain the most detailed instructions of the Amdwat, how to get there, and the correct use of incantations essential for the soul to maintain focus throughout the journey. Its influence resonates throughout all ancient Mysteries schools. But above all, the Pyramid Texts imply they were intended as a ritual where the initiate was expected to return to the living body.

The texts cover the innermost chambers of Unas’ 2350 BC pyramid, and like Thutmosis III’s chamber, Unas’ necropolis contains a sarcophagus but no evidence of his burial. Indeed the building is designed as a ritual complex, originally accessed from the east bank of the Nile by a boat ferrying the initiate, who disembarked in the west into a valley temple, proceeded along a covered causeway leading into the subterranean temple and under the pyramid. After residing in the womb-like chamber for a prescribed period, the candidate reappeared at dawn at the summit of this man-made hill. From the outset the candidate followed the figurative path of the descending Sun into the Otherworld.

Every aspect of Unas’ complex involves ritual symbolism: his black granite sarcophagus lies symbolically in the west; granite was the material of choice because, as an igneous rock emanating from within the earth in a molten state, it effortlessly mimics the soul’s immersion in the void, changing from liquid to solid as it re-enters the physical world following a transfiguration. The choice of black carries a further significance in that it is the color associated with spiritual resurrection.

Far from being mere funerary beliefs, the Pyramid Texts represent a mystical experience akin to that described in shamanism, such as the ascent of the soul and the spiritual rebirth of the individual. What defines them as an instruction meant for a person undergoing a figurative rather than a literal death is encompassed in Utterance 213, the one closest to the sarcophagus: “O Unas, you have not departed dead, you have departed alive to sit upon the throne of Osiris, your aba scepter in your hand that you may give orders to the living.” Clearly the pharaoh has ascended into the Amdwat alive and is capable of communicating with the living and the discarnate alike. A second clue is the section where Unas undergoes spiritual purification and rebirth to a chorus of “Unas is not dead, Unas is not dead,” and the return of his spirit back into his living body. No other utterance so encapsulates the central theme common to all Mysteries traditions: that the soul is capable of disengaging from the living, physical body, journeying independently into the spirit world and returning.

Continue to part II

Return to Articles

Indra, resurrected god-man of Nepal c.500 BC.. From a 17th century manuscript.