LIVING RESURRECTION:

an initiate's best-kept secret

part II

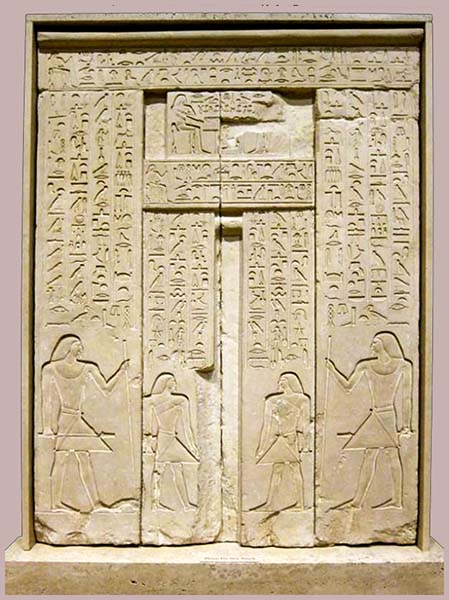

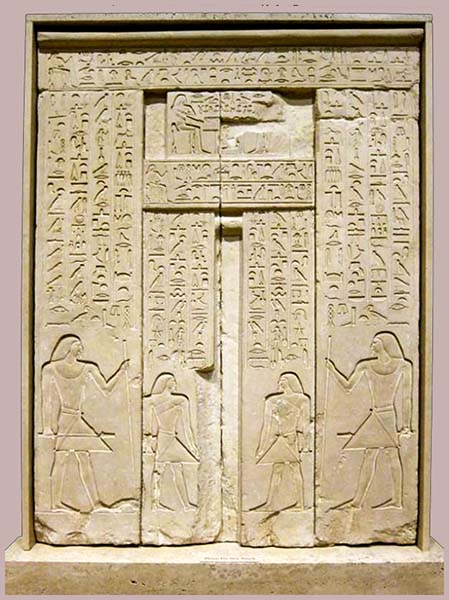

At Saqqara there is a recurring theme of the living resurrection ritual. An inscription on a ka door (a false door reserved for the soul — see image above), describes the surprise by a servant in pharaoh Teti I’s household at joining this privileged inner circle “to master secret things of the king.” Teti built his pyramid beside that of Unas and contains part of the latter’s Pyramid Texts. The humbled servant continues: “Today in the presence of the son of Ra, Teti...more honoured by the king than any servant, as master of secret things.... When his majesty favoured me, he caused that I enter the chamber of restricted access.” At the end of his ritual experience, this individual proclaims, “I found The Way.”

The Way or Tao was a ritual of self-realization practiced by Mysteries schools of ancient Japan and China in 2600 BC, as well as in Persia, Ireland and Native America; it was later adopted by the Mandeans and the Essenes, with whom John the Baptist and Jesus were involved. While the popular version of the legend has Jesus hailing from Nazareth, nothing could be further from the truth, for Nazareth consisted of little more than a few hovels and caves. What did exist was the title nasoraiyi and it was the title of certain members of the inner brotherhood of the Mandeans.

The name derives from the Babylonian nasiru, meaning ‘preserver of divine secrets’, and it was awarded to an initiate who’d achieved the highest grade of initiation following a ritual in a secret “bridal chamber” whereupon the successful candidate was declared ‘raised from the dead’. Only they were officially qualified to administer that most secret of rites, the living resurrection. Later, Jesus joined such a sect before forming his own sect with his nasoraiyi, who were based in the town of Cochaba.

When a new religion was brought to Rome in the first century, with Yeshua ben Yosef occupying the role of resurrected hero, the story didn’t fare well with a populace accustomed to deifying its heroes. Nor did it wash with the Gnostics of Greece, Asia Minor and Egypt, who considered this man Jesus to have been a mere mortal, and never crucified much less reincarnated from a physical death. The proponents of such heresies were bishop Marcion of Sinope, Valentinus of Alexandria, and the scholar Basilides, who claimed the crucifixion was a fraud — that a substitute named Simon of Cyrene took Jesus’ place.

Manuscripts written within a century after Jesus’ time and rediscovered at Nag Hammadi claim as much. One of them, Second Treatise of the Great Seth, is particularly damning because it quotes Jesus in the first person describing the crucifixion: “I did not die in reality but in appearance, lest I be put to shame by them.... For my death which they think happened, happened to them in their error and blindness, since they nailed their man unto the death.... It was another, their father, who drank the gall and the vinegar; it was not I...it was another, Simon, who bore the cross on his shoulder. It was another upon whom they placed the crown of thorns.... And I was laughing at their ignorance.”

The Etruscan resurrected go-man Ixion ‘crucified' on a solar wheel, hundreds of years before Jesus.

Sekhemkhet’s pyramid lies in Saqqara, a sprawling ceremonial temple complex named for Seker, falcon god of Even as late as the 7th century the Quran upheld the same argument: “And their false allegation that they slew the Messiah, Isa, the son of Maryam, the Messenger of Allah, when in fact they never killed him nor did they crucify him.”

Most damning of all is Pope Leo X’s admitting that the story of Jesus was a myth: “All ages can testifie enough how profitable that fable of Christ hath been to us and our companie.” Nevertheless a literal view of the resurrection was leveraged by the Church, whose authority relied on the experience by a closed group of apostles of Jesus’ miraculous regeneration, and the position of incontestable authority the event bestowed upon them. Since Peter was the first witness, and the Pope came to derive his authority from him, it was in the Church’s best interests to promote a literal spin on resurrection.

The position was helped by the apostle Paul’s misunderstanding of Jesus making dead people return to life — which he’d never been privy to — and the First Epistle to the Corinthians nearly lets the cat out of the bag when it notes that Paul was “determined to know nothing but Jesus Christ and him crucified;” in other words, Paul sought to deny the existence of earlier, established myths of risen god-men.

Continue to part III

Return to Articles